What This Senior Developer Learned From His First Big Rust Project

Building a Rust IoT MVP over the Holidays

[ history ]Here is a bit of background on me

- according to my company's org chart on Workday, my current title is "Senior Consultant"

- I've been writing code full-time in various capacities for over a decade and I've been professionally developing software for about five years

- in graduate school, I did data analysis and visualization almost entirely in C++

- for the last four years, my primary development language has been Scala

This blend of "close-to-the-metal" development in C++ and FP-style development in Scala has led me to Rust, which I see as a pretty usable middle ground between the two. So over the past year I've been learning Rust by building small projects and leading weekly book clubs.

Over the holidays, I decided to take this a step further and build my first "big" Rust project. Here's how that went down...

TL;DR: if you're only interested in the technical discussion, and not so much the project background, skip to the section on implementation. If you just want my conclusions, skip to the end.

The Project

The idea I had was to build a small Internet of Things (IoT) system. The explicit goals of the project were

- to build some services which used very few resources, capable of running in environments where the size of the Java Runtime Environment (JRE) would make Scala or Java development impossible

- the services should run on separate nodes and somehow discover each other on the network, without the need for hard-coded IPs

- the services should be able to send messages to (and receive messages from) one another

- there should be some simulated data in the system, which can be visualized (or, at least, exported to a spreadsheet for visualization)

In addition, I work for a consulting company, and the client we are engaged with was OOO over Christmas. So another goal of this project was to have all of this completed, from scratch, in just five working days.

I managed to recruit two other developers* who helped build some of the foundations of the project in those first five days; in the two weeks since, I've built out the rest of the project by myself. In general, I consider the effort a success, but am hoping that whoever reads this might be able to leave some valuable feedback which could improve future efforts of this kind.

* Huge shout-out to boniface and davidleacock!

Planning

The other two developers and I spent the week before Christmas planning and discussing the project, but not coding. We were hoping that "team of three developers builds a Rust IoT MVP in just five days" would be an effective sales tool for ourselves and our company. It was very ambitious, and the work soon spilled over into about four person-weeks total (which is still not bad, if you ask me).

I prepped by writing some sketches, as I called them. These were little projects that (I'd hoped) would become the building blocks of our MVP. These sketches included

- learning how to build a CI pipeline in GitHub Actions

- learning how to build a CD pipeline in GitHub Actions

- writing two containerized services in Rust which communicated with each other over a network

- writing two containerized services which discovered each other via mDNS

I also created a custom Rust-based container image for the CD project, which includes the necessary libraries for the CI project, like

rustfmtfor formatting,clippyfor linting, andgrcovfor code coverage reporting.

While I originally thought of containerizing these applications, running them in Kubernetes (K8s), and letting K8s do the service discovery, I realized that that approach wouldn't square with "real life", where the services would somehow have to discover each other on a LAN. mDNS seemed the best choice to emulate real-life service discovery on a network.

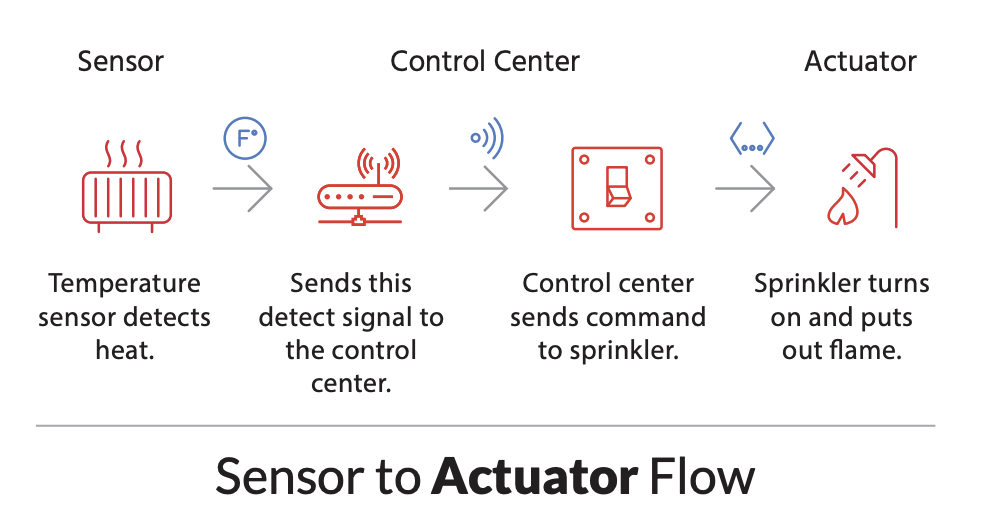

Finally, we had to plan the domain itself. We came up with something quite similar to this example from Bridgera

- a

Sensorcollects data from theEnvironment, and somehow communicates that data to... - a

Controller, which assesses that data and (optionally) sends aCommandto... - an

Actuator, which has some effect on... - the

Environment, which, in our example, generates fake data and has some internal state which can be modified viaActuatorCommands

These four kinds of Devices -- Sensors, Actuators, and the Controller and Environment, are the services in this system. They connect to each other via mDNS.

As we were short on time and resources, all of this was to be done in software, with no actual interaction with any hardware sensors or actuators. Because of this, we needed a simulated Environment, which could generate fake data for our Sensors.

From the outset, we realized it was important to have Ubiquitous Language around these concepts. We worked to refine and document our understanding of the domain, and keep our model as clear and as small as possible. Nothing unnecessary or confusing should sneak through.

Implementing

Anyway, down to the nitty-gritty.

Cargo Workspace

This project is structured as a Cargo workspace, where there are multiple crates in a single repo. The idea behind this was that, in a real-life scenario, we would want to publish separate library crates for Actuators, Sensors, and so on. If you are a third-party developer creating software for (for example) a smart lightbulb, you might not care about the Sensor library. Your device only has an effect on the environment, it doesn't probe it in any way.

Setting up a project as a Cargo workspace is straightforward, and allows you to pull out "common" code into one or more separate crates, which adheres to the DRY principle and just generally makes the whole project easier to develop and maintain.

Dependencies

In the interest of keeping the resulting binaries and containers as small as possible, I steered this project away from the big frameworks (tokio, actix, etc.), opting to "roll our own" solutions wherever we could. Currently, the project has only eight dependencies

mdns-sdfor mDNS networkingchronofor UTC timestamps and timestamp de/serializationrandfor random number generationlocal-ip-addressfor local IP address discoveryphffor compile-time staticMapslogtherust-langofficial logging frameworkenv_loggera minimal logging implementationplotlyfor graphing data in the Web UI

Even some of these are not strictly necessary. We could

- do away with

chronoby rolling our own timestamp de/serialization - remove

phfby just creating this single staticMapat runtime - do away with

logandenv_loggerby reverting to usingprintln!()everywhere

mdns-sd and local-ip-address are critical; they ensure the Devices on the network can connect to one another. rand is critical for the Environment, and appears only in that crate's dependencies. plotly is critical to the Web UI, hosted by the Controller, which (as of this writing) shows just a live plot and nothing else.

Finally, for containerization of services, we used rust:alpine base image in a multi-stage build. Only a single dependency needed to be installed in the initial stage, musl-dev, which is required by the local-ip-address crate.

The final sizes of the four binaries produced (for the Controller, Environment, and one implementation each of the Sensor and Actuator interfaces) ranged from 3.6MB to 4.8MB, an order of magnitude smaller than the JRE, which clocks in around 50-100MB, depending on configuration.

The containers were a bit larger, coming in around 13.5MB to 13.7MB. This is still peanuts compared to container image sizes I'm used to for Scala-based projects -- I find that Scala container images are typically in the 100s of MBs range, so < 15MB is a breath of fresh air.

Service Discovery and Messaging

As this sketch shows, it's actually really straightforward to get two services to discover each other via mDNS with the mdns-sd crate. Once services knew about each other, they could communicate.

The easiest way that I know of for two services on a network to communicate with each other is over HTTP. So in this project

- Service A discovers Service B via mDNS, retrieving its

ServiceInfo - Service A opens a

TcpStreamby connecting to Service B using the address extracted from itsServiceInfo - every service (including Service B) opens a

TcpListenerto its own address, listening for incoming TCP connections - Service A sends a

Messageto Service B via itsTcpStream, Service B receives it on itsTcpListener, handles it, and sends a response to Service A, closing the socket

These Messages don't necessarily need to be HTTP-formatted messages, but it makes it easier to interact with them "from the outside" (via curl) if they are.

Similarly, the data points (called Datums in this project) sent via HTTP don't need to be serialized to JSON, but they are, because it makes it easier to interact with that data in a browser, or on the command-line.

Construction of HTTP-formatted messages and de/serialization of JSON was all done by hand in this repo, to avoid bringing in unnecessary dependencies.

TIP: one "gotcha" I encountered in writing the service discovery code was that each service needs its own mDNS

ServiceDaemon. In the original demo, a single daemon was instantiated andclone()d, with the clones passed into each service. But then only theActuator(or only theSensor) would see, for example, theEnvironmentcome online. It would consume theServiceEventannouncing that device's discovery on the network, and the next service wouldn't be able to see it come online. So, heads-up: create a separate daemon for each service which needs to listen to events.

Common Patterns and Observations

With the basic project structure in place, and with the services able to communicate, I noticed a few patterns reoccurring as the project came to life.

Arc<Mutex<Everything>>

In this project, the Devices have some state which is often updated across threads. For instance, the Controller uses one thread to constantly look for new Sensors and Actuators on the network, and adds any it finds to its memory.

To safely update data shared across multiple threads, I found myself wrapping lots of things in Arc<Mutex<...>> boxes, following this example from The Book.

I'd be interested in knowing if there's a better / more ergonomic / more idiomatic way of doing this.

Cloning before move-ing into a new thread

Another pattern that appears a few times in this repo is something like

fn my_method(&self) {

let my_field = self.field.clone();

std::thread::spawn(move || {

// do something with my_field

})

}

We cannot rearrange this to

fn my_method(&self) {

std::thread::spawn(move || {

let my_field = self.field; // will not compile

// do something with my_field

})

}

because "Self cannot be shared between threads safely" (E0277). Similarly, anything wrapped in an Arc<...> needs to be cloned as well

fn my_other_method(&self) {

let my_arc = Arc::clone(&self.arc);

std::thread::spawn(move || {

// do something with my_arc

})

}

I've ended up with a few thread::spawn sites with big blocks of cloned data just above them.

There's an RFC for this issue, which has been open since 2018. It looks like it's making some progress lately, but it could be a while before we no longer need to manually clone everything that gets moved into a thread.

It's too easy to .unwrap()

This project is not very large -- it's about 5000 lines of Rust code, by my estimate. But in those 5000 lines, .unwrap() appears over 100 times.

When developing something new, it's easier (and more fun) to focus on the "happy path" and leave exception handling for later. Rust makes this pretty easy: assume success, call .unwrap() on your Option or Result, and move on; it's very easy to bypass proper error handling. But it's a pain in the neck to add it in later (imagine adding error handling for all 100+ of those .unwrap() sites).

It would be better, in my opinion, to keep on top of these .unwrap()s as they appear.

Near the end of this MVP, as I counted all of these sites with missing error handling, I found myself longing for a clippy rule which would disallow any .unwrap()...

As it turns out, there already are unwrap_used and expect_used lints which can be used to error out if either of these methods are called. I will definitely be enabling these lints on my personal projects in the future, and I hope that they will eventually become the default.

Parsing

I wrote a lot of custom parsing code.

A common pattern I followed was to impl Display for some type, then add a pub fn parse() method to turn the serialized version back into the appropriate type.

This is probably not the best way to do this -- user-friendly strings for display are different things from compact serialized representations for message passing and persistence. If I were to do this again, I would probably use a crate like serde for de/serialization, and save impl Display for a user-friendly string representation.

In addition, I "rolled my own" routing. When an HTTP request was found on a TcpStream, I would manually check the start_line (something like POST /command HTTP/1.1) to route to the appropriate endpoint. In the future, I might leave this to an external crate... maybe something like hyper.

pub structs should implement PartialEq when possible

I think this is probably a good rule of thumb for any pub data type: implement PartialEq when appropriate, so consumers of your crate can test for equality. The ServiceInfo type in mdns-sd does not derive PartialEq. This means I couldn't easily test for equality of two ServiceInfos in tests.

In lieu of this, I checked that every pub method on two instances returned the same values. This was kind of a pain, resulting in big blocks of

assert_eq!(actual.foo(), expected.foo());

assert_eq!(actual.bar(), expected.bar());

assert_eq!(actual.baz(), expected.baz());

// ...

It would have been nice to just write

assert_eq!(actual, expected)

instead.

traits implementing other traits can get messy, fast

In this project, there's a trait Device with an abstract method called get_handler()

// examples in this section are abridged for clarity

pub trait Device {

fn get_handler(&self) -> Handler;

}

The Sensor and Actuator traits both implement Device, and provide default implementations of get_handler()

pub trait Sensor: Device {

fn get_handler(&self) -> Handler {

// some default implementation here for all `Sensor`s

}

}

pub trait Actuator: Device {

fn get_handler(&self) -> Handler {

// some default implementation here for all `Actuator`s

}

}

But then there are the concrete implementations of Sensor and Actuator

pub struct TemperatureSensor {

// ...

}

impl Sensor for TemperatureSensor {}

impl Device for TemperatureSensor {

fn get_handler(&self) -> Handler {

Sensor::get_handler(self)

}

}

pub struct TemperatureActuator {

// ...

}

impl Actuator for TemperatureActuator {}

impl Device for TemperatureActuator {

fn get_handler(&self) -> Handler {

Actuator::get_handler(self)

}

}

There already is a concrete implementation of get_handler() in Sensor / Actuator, so we don't actually need anything in the impl Sensor / impl Actuator blocks (unless there are other abstract methods), but we do need this awkward impl Device in each case.

As far as Device "knows", TemperatureActuator hasn't implemented its abstract method. But we know that Actuator has, and that TemperatureActuator implements Actuator. There seems to be some information missing here that the compiler could fill in, theoretically, but currently isn't.

Rust could use a more robust .join() method on slices

Other languages let you specify a start and end parameter when joining an array of strings, so you could easily do something like

["apple", "banana", "cherry"].join("My favourite fruits are: ", ", ", ". How about yours?")

// |--------- start ---------| |sep| |------- end -------|

which would result in a string like "My favourite fruits are: apple, banana, cherry. How about yours?", but Rust doesn't yet have this functionality. This would be a great little quality-of-life addition to the slice primitive type.

All of my Result error types are Strings

This is certainly the easiest way to quickly build something while mostly ignoring failures, but at some point, I should go back and replace these with proper error types. Clients should be able to match on the type of the error, rather than having to parse the message, to figure out what failed.

Any Result types which leak to the external world (to clients) should probably have proper Err variants, and not just String messages. This is another thing I wish clippy had a lint for: no &str or String Err types.

S: Into<String> instead of &str

Rust will automatically coerce &Strings to &strs, and so the traditional wisdom is that function arguments should be of type &str, so the user doesn't need to construct a new String to pass to a function which takes a string argument. If you already have a String, you can just call as_ref() on it to get a &str.

But Rust will only do a single implicit coercion at a time. So we can't convert some type T: Into<String> into a String and then into a &str. This is why I opted for S: Into<String> instead of &str arguments in a few places. &str implements Into<String> and so does any type which implements Into<String> (or Display).

It is definitely less performant, since we're copying data on the heap, but also a bit more ergonomic, since we don't need to pass t.to_string().as_ref() (when t: T and T: Into<String>) to the function, but just t itself.

Apparently I'm not the first person to discover this pattern, either: Into<String> returns 176,000 hits on GitHub.

Conclusion

I learned a lot in building this project: about mDNS networking, the nitty-gritty of HTTP message formats, and writing bigger projects in Rust. To summarize the points I raised above...

Things I know I need to do better

- I shouldn't be using

Displayfor serialization. In the future, I will look into using a crate likeserdeinstead. - I shouldn't be using

Stringfor all of myErrvariants. Clients of the library crates I'm producing should be able to handle an error without having to parse a string message. In the future, I will build errorenums as soon as I start producing errors.

Things I'm looking forward to from the Rust community

- Explicit

clone-ing prior to amoveclosure is a pain. I'm following this GitHub issue in hopes that this becomes more ergonomic in the future. - A

clippyerror forString/&strErrvariants would be nice, as well. - Rust could use a more robust

.join()method on string slices, withstartandendparameters. As far as I can tell, this issue is not yet being tracked. After this article is published, I hope to open an RFC for this small feature. - I'm hoping that eventually the compiler will be smart enough to know that when

B: AandC: B, whereAdefines some abstract method andBimplements that abstract method, thatc: Calready has that method implemented, without having to explicitly tell the compiler about that implementation. But that might be a ways off.

Things I still have questions about

- Is

Arc<Mutex<Everything>>really the best way to mutate data across multiple threads? Or is there a more idiomatic (or safer) way of doing this?

Things I would recommend to other Rust developers

- Please

implPartialEqon anypubdata type published by your crate, whenever possible. Your clients will thank you (hopefully). - Don't be afraid to use

S: Into<String>instead of&str. It might be less performant, but it's also more ergonomic, and you're definitely not the first person to do it. - Enable

clippy'sunwrap_usedandexpect_usedlints, to force yourself to tackle error scenarios head-on, instead of pushing them aside to deal with them later.

If you've made it this far... thanks for reading!

Please direct any feedback you may have about the above article to the email address on my CV. This was a fantastic learning experience and I'm excited to do some more serious Rust development in the near future.